Conventions in portraiture are much concerned with identifying social category. These Elizabethans can’t have been interested in making themselves the subject of some artist’s sensitive exploration of personality; they wanted their images to evoke grandeur. The more an earl’s portrait resembled a duke’s, the better he’d be pleased.

The same objective, group identification, applies to the War Gallery at the Hermatage.

![the War Gallery of 1812 at the Hermatage [ekaterina-voyage]](http://www.stanwashburn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/the-War-Gallery-1812-ekaterina-voyage.jpg)

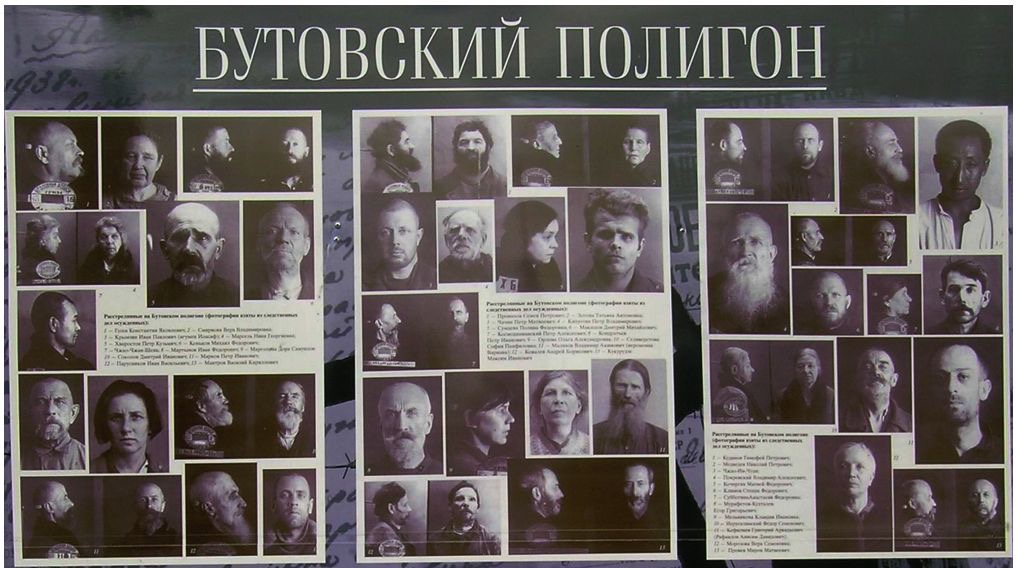

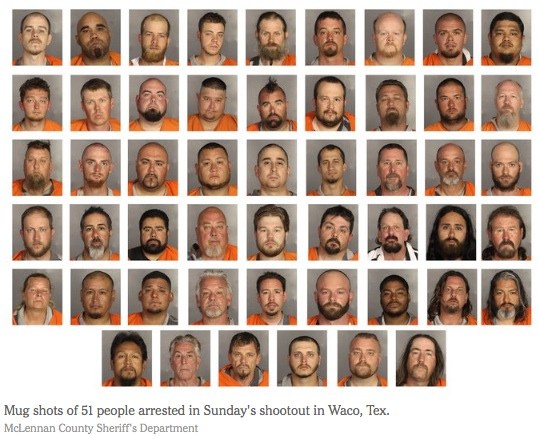

Of course, nobility and generals aren’t the only ones whose uniform representations are impressive en masse:

![[nytimes.com]](http://www.stanwashburn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/cosby-nytimes.com_.jpg)

![Life Magazine 6/27/69 [sajunk.wordpress.com]](http://www.stanwashburn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Life-6_27_69-sajunk.wordpress.com_.jpg)

![Ai Weiwei "The Fake Case" [youtube]](http://www.stanwashburn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Ai-Weiwei-_the-Fake-Case_-youtube.jpg)

Years ago I saw a small book–“Uniforms,” I believe, was the title. There was almost no text; it consisted of full-page photos of similarly dressed groups: bikers of various persuasions, gays, lesbians, mechanics, sports fans, groups of teenagers, different groups of teenagers, different bands of bikers, and on and on. We see those patterns every day, but to see so many examples in the same format, one right after another, was fascinating. I would include some examples here, but like a fool I didn’t buy the book, and haven’t been able to locate a copy since.