We are taught to admire strong art, but not to notice how different it is from daily life, or why. The difference is that art is after something specific.

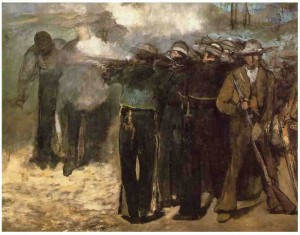

So here we have Goya’s famous painting of French troops executing rebellious Spanish civilians during the Napoleonic wars. Goya arranges the elements so that we get his point at a glance. The firing squad is anonymous and professional. The victims are a softly rounded cluster of individuals centering on the white-shirted man in the center. He is the predominant figure because his shirt sets him off, his face is the one we see clearly, and he is the focus of the visual arrowhead formed by the ground rising from the lamp, and the line of slightly depressed muskets. He raises his hands, seemingly not so much for mercy as in disbelief. Expressed or implied, disbelief is a recurrent theme in Goya’s work, as in the drawing to the right. It is, presumably, his point here. It’s a good point, and powerfully made, in part because of

Goya’s reserve as an artist. The message is the focus. You get the hit; only then, if you care to, do you analyze how he creates his effects. Goya’s technique is dynamite, but it’s not what you notice.

As compared to this Picasso, which quotes from both the Goya and the Manet next to it. But its triple-barreled ray-guns and stylish imagery cry out “hot art!” louder than anger or pity. As a result it has no emotional impact to speak of—with the exception of the calm, central female figure, lifted, it seems, from the figure of Maximilian in the Manet.

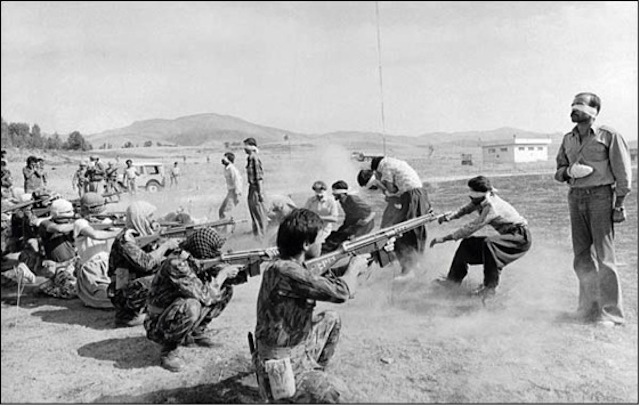

Of that figure, strangely enough, we encounter a moving reprise in this photo from revolutionary Iran: the man on the right, the dominant figure, orderly and dignified in the moment before death. Only his clenched left hand betrays his tension.

How similar this scene is to Goya’s, but how unlike. What, exactly, strikes us? Without Goya’s focus, we have to think about it. The bearing of the victims? The clownish amateurs of the firing squad? Or the little gaggle of spectators, the casually parked jeep, the nondescript landscape with that distracting white building? The photo is evidence, not summation. We are left to apply our own predispositions, and draw our own conclusions—an exercise of judgment that Goya, in the case of the 3rd of May, has preempted in order to make his point.